There was a childhood game that I played with my father when I was a boy. It stemmed from the fact that he wasn't always allowed to see or call me, being as there were frequent disputes between he and my mother. So he would sometimes show up unannounced at my school with some imaginary emergency and we would sit for a few minutes in some school administrator’s office pretending to be solemn for the audience on the other side of the window as we talked about the adventures of our respective lives. Or, my favorite, when he would call me in the predawn hours of the morning before anyone else was awake, and before the first ring was complete there I was with the phone to my ear waiting for the code words, “this is me, is that you?” and always in some strange, disguised voice that he would invent just for the occasion.

I would repeat the words and we would share a quiet, conspiratorial laugh as the prelude to the game that we most enjoyed where we would each invent the most fantastical stories imaginable and every phone call or visit was another chapter to the invented saga. We both contributed to the storylines, but he was the one who created the magic that was like fireworks to my imagination. And I loved him for it.

Anyone whose childhood knew divorce knows a thing or two about the stigma that comes from being a “broken” family. The underlying implication is that we’re somehow defective or tainted by our parents’ marital challenges or failures, as though those failures were somehow contagious. You see it on the countenances of the other parents when you're invited over for dinner or the sleepover—often for the first and last time.

By the time I was 6, I was an expert at controlling conversations with parents so that they never asked what I didn't want them to. I was engaging, witty, sympathetic, and basically an expert conversationalist. Like an improv performer on stage I was tasked with entertainment, but the stakes seemed much higher. Perhaps because, although nobody was applauding me and I wasn't being paid, what was at stake was their acceptance and that all too familiar shift on their countenances from pity, to fear, to a sort of distaste that borders on repugnance.

I once saw my dad observe my act of conversational misdirection, and at the time I had the sense that I was doing something wrong and that at any moment he would step in to chastise and correct me. But he didn't, at least, not then, but there was a sadness in his eyes that hadn’t been there before when he came to tuck me in and wish me a good night. And I will never forget how uncomfortable I felt seeing him watch me adroitly perform conversational acrobatics for nothing more than avoiding those all too typical statements of I'm so sorry to hear that, or my favorite, that’s too bad, and yet you're so well behaved.

People assumed that because my parents were divorced that my behavior should have been that of a child mercenary in route to a juvenile detention center before puberty. Which, in all fairness, was a common trait amongst children of other divorced parents. And that, of course, made me all the more adamant to avoid anything stereotypical—i.e., I was frequently the most polite, well behaved, engaging child in the room; I saw it as a sort of competition, a way to distinguish myself from the others.

From ages 5 to 10, there wasn't a day that went by that I didn't implore God for my parents to get back together. Though, the more I seemed to pray on the matter the less probable it became. In fact, by my tenth birthday my mother’s patience for my dad's unwillingness to live up to his financial responsibilities had reached a boiling point and he wasn't allowed to come into the house. He had a gift for me and I was only permitted to sit in the car with him while she observed us from the porch to make sure he didn't take me.

The injustice of the predicament was more than I could bear, and there in the passenger seat of a borrowed car I began to cry. He didn't say anything, at first, other than to give me his handkerchief and then my gift. But I wasn't interested in opening presents and probably wouldn't have done so had he not insisted.

“Open it,” he said. “I promise you'll feel better when you do.”

Over my sobs and through his insistence I opened my gift to find a rather expensive pen and pencil set. On our weekends together I would often sit at his desk and write with his pens and pencils, always with great care so as not to damage the tips. He had always told me that when I was old enough he would get me my own pens, but to my young mind and eager spirit it felt like another empty promise. But it wasn't, and I was ecstatic, mostly because he hadn't forgotten what I most wanted.

“Son,” he began, as I wiped my tears and marvelled over the writing instruments in my hands, “by now you know that your mother and I can't be together. I know that you're angry, ashamed, frustrated—and you shouldn't be. Childhood should be a magical time for you, and you shouldn't have to deal with these types of problems, but since you are dealing with them, there is something you should know.

“If you spend your life living by what other people think of you, you'll wake up one day to find that you haven't lived your life yet and somehow the best of it is already gone. Don't do that. And don't waste even a second of your life trying to convince someone to believe what you believe. Your truth is yours because you've lived it and nobody can take that from you. Unfortunately, as I'm sure you're figuring out, life rarely waits until we're ready, and most of what will happen to us will be unpleasant, maybe even horrible. But even that's not a good enough reason to give up on it.”

I knew his childhood had been hard. Which was to say that his mother had padlocks on her cupboards and would frequently lock him in an old shed on the property. Whether there were physical beatings involved, I never knew, but I knew that a substantial amount of his childhood was spent alone, in the dark, in the cold, being fed tortillas from under the door by his older sisters who would sneak in to feed him. By this time in life I already knew what it was like to feel helpless. I had older stepbrothers who made it a point to physically beat or molest me at every opportunity—a secret that I kept for too long. But one that I kept because to reveal it would have essentially poured gasoline and lit the match on my mom's new relationship, happiness—not to mention, destroy any semblance of normality we had achieved in outward appearances.

One of the things that I most loved about him is that he always seemed to intuit my fears and struggles and he never made me talk about them. I promised him that I wouldn't give up, that I'd be as strong as Superman. But he just smiled sadly and said that he wished it was that easy. I tried to get him to play the game with me, the one where we took turns with the storylines, but he looked over and saw the impatient fury on my mom's face and opted otherwise. Instead, he hugged me and said something that would carry me through some of the darker moments to come.

“Son, always remember that childhood is temporary. Today you do what you're told, but there will be a tomorrow when you'll have the world at your fingertips.”

As a child I didn't recall anyone who loved or knew him who openly talked about his struggle with alcoholism, and in that sense I know that we all failed him. The challenge for everyone could have been, that, in those days, alcoholism wasn't diagnosed as the illness it is today. And looking back, maybe I should have said something. But for the briefest of moments that I had him lucid I wanted more than anything to be with the dad who so adroitly created those imaginary worlds where dragons, wizards, dwarves, elves and so many other magical creatures existed; the dad who had answers to every question, and who was never too impatient to show me anything for the umpteenth time.

He was an alcoholic and I was his son, and despite our limitations we had some of the greatest adventures imaginable together. The moments we shared were lived as though any one of them could have been the last. And yet, there was something tragic about watching his life sink into ruins and doing nothing to stop it.

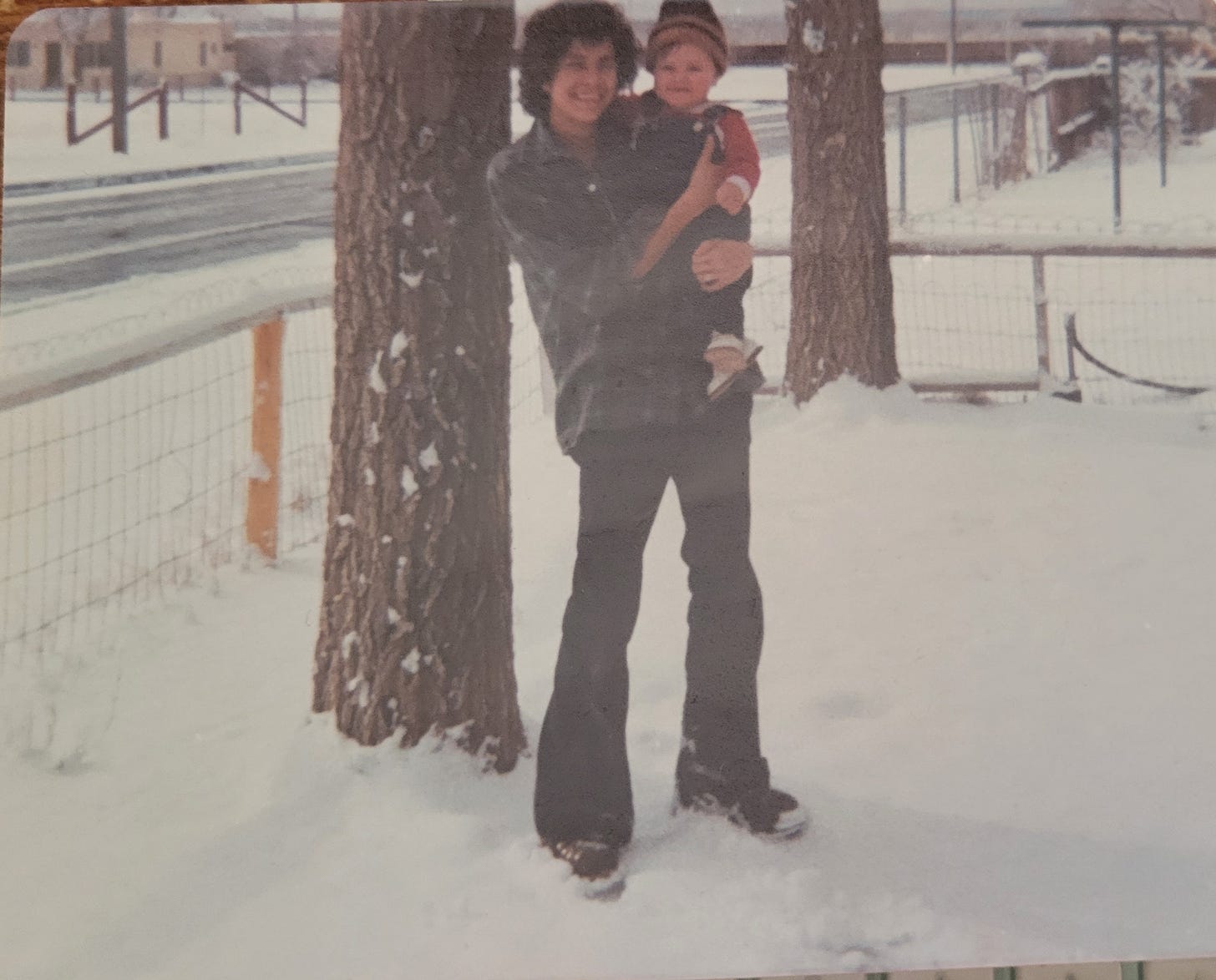

Frequently, he had no car to take us places. So he would take a cushion and sit me sideways on the center bar of his emerald green 10 speed and proceed to peddle us everywhere we wanted to go for our weekends together. And in those moments I couldn't have imagined a better dad, childhood, or mode of transportation.

He was intelligent—gifted in drafting, electronics, accounting, a natural salesman, a classic overpromiser, and an avid reader. His superpower was his charisma and he knew how to relate to just about anyone. But even his superpower couldn't rescue the friendships and relationships evaporating from his life as quickly as the bottles of booze were emptying. And our relationship was definitely not immune to the sickness eating through his life.

Too many times he left me sitting outside my mothers apartment with my backpack waiting for him to pick me up. My mom would often tell me that he had called and said that he wasn't going to make it, but I never believed her and just assumed that either she had told him not to come or that she was trying to convince me to do something else so I wouldn't be there when he showed up.

I would sit there for hours on the sidewalk, and, at first, nothing or nobody could convince me that he wasn't going to show. I couldn't conceptualize how he could love me and at the same time fail to be there and keep his promise. And the more he failed me, the more the magic between us dissipated.

A dissipation that deprived him of most of my adolescence. The only memory I have of him from that time period was an unexpected phone call I received after months of silence. He wanted to know if he could visit to bring me a gift. Mom was hesitant, but as she looked over at the eagerness on my face, she agreed.

Surprisingly he showed up later that afternoon with a paper bag in his hand. The gift in question was a Gillette razor and a can of shaving cream. He took me to the bathroom and showed me how to shave the baby fuzz from my face. I remember smelling the beer on his breath, and usually I would have a million things to say—anything to keep him from leaving—but this time when he said he had somewhere to be, I just hugged him, and suddenly there were no more tears.

He didn't come around very much after that. Or if he did, I don't remember. My memories of him from that time period are scattered. He would sometimes have me over for the weekend and then leave me watching television while he spent time with a girlfriend. Or he would take me with him to billiard halls and bars and introduce me to his new transient friends and family. I hated those weekends and would frequently find a way to call my mom, and in a whisper, beg her to come get me. He always appeared disappointed that I didn't want to stay with him, and I just didn't know how to explain in a way that wouldn't hurt him that I was embarrassed to be his son.

One of our favorite pastimes from childhood was hiking and camping. But now, if we went at all, he would always bring some woman and her kids. They didn't know the games or the storylines, and they certainly weren't going to sleep on the ground, eat dinner that was hunted or scavenged, or hike for miles on end for no other reason than because we could. Instead, we would just sit by a creek with a postcard panorama eating food from a cooler. He would walk with his girlfriend and I was left performing the role of mountain guide to her tourist children.

The only good part for me was receiving my dad's conspiratorial grin and nod of approval. Nevertheless, these excursions were not frequent and as I got older I had my own girlfriends, after school jobs, clubs and projects at school, and very little time for his broken promises.

The only person in my young life who knew how much he hurt me and how much I missed him was my mom. And she certainly never got the credit she deserved for the extraordinary lengths she went to making sure I still did things like camping and fishing in his absence. She would organize these excursions where there were always lots of friends and family with plenty of food, music, games—something like a traveling carnival. I admit that I look forward to those trips because she would always let me invite friend. And once the festivities were underway we could enjoy wilderness adventures with hiking, climbing, spear fishing, or hunting with slingshots.

Eventually I was inviting my own girlfriends and began to understand why my dad had done it. But he was rarely present in my life by the time I was driving and dating. And if I wanted to find him I would have to track him down through his sisters, places of employment, or former residences.

By the time I was a teenager the magic he had created in my childhood was a distant mare memory. I no longer believed in most of what he said, and when I went through the trouble of finding him it was usually because I needed tuition, clothes, or just money for any number of school activities and my mom's standard answer was always, “ask your dad!”

I would often find him working as a bartender in some dive, or as an airport parking attendant on the graveyard shift. And to see him in those positions didn't help to raise my opinion of him, but not because of the mediocrity of the jobs themselves, but because I knew that his whole reasoning for subsisting in second rate jobs instead of thriving in any number of careers that he was qualified to pursue was because he refused to pay what the courts had ordered as child support.

His sisters would sometimes pay my tuition bills because my mother couldn't handle it on her own. Add to that my wanting to play the violin, sports, and any other activity that interested me and the precarious nature of my mom's financial picture starts to come into focus. And eventually it just got to the point where she had to tell me no, and I’m ashamed to admit that I gave her a lot of grief for it.

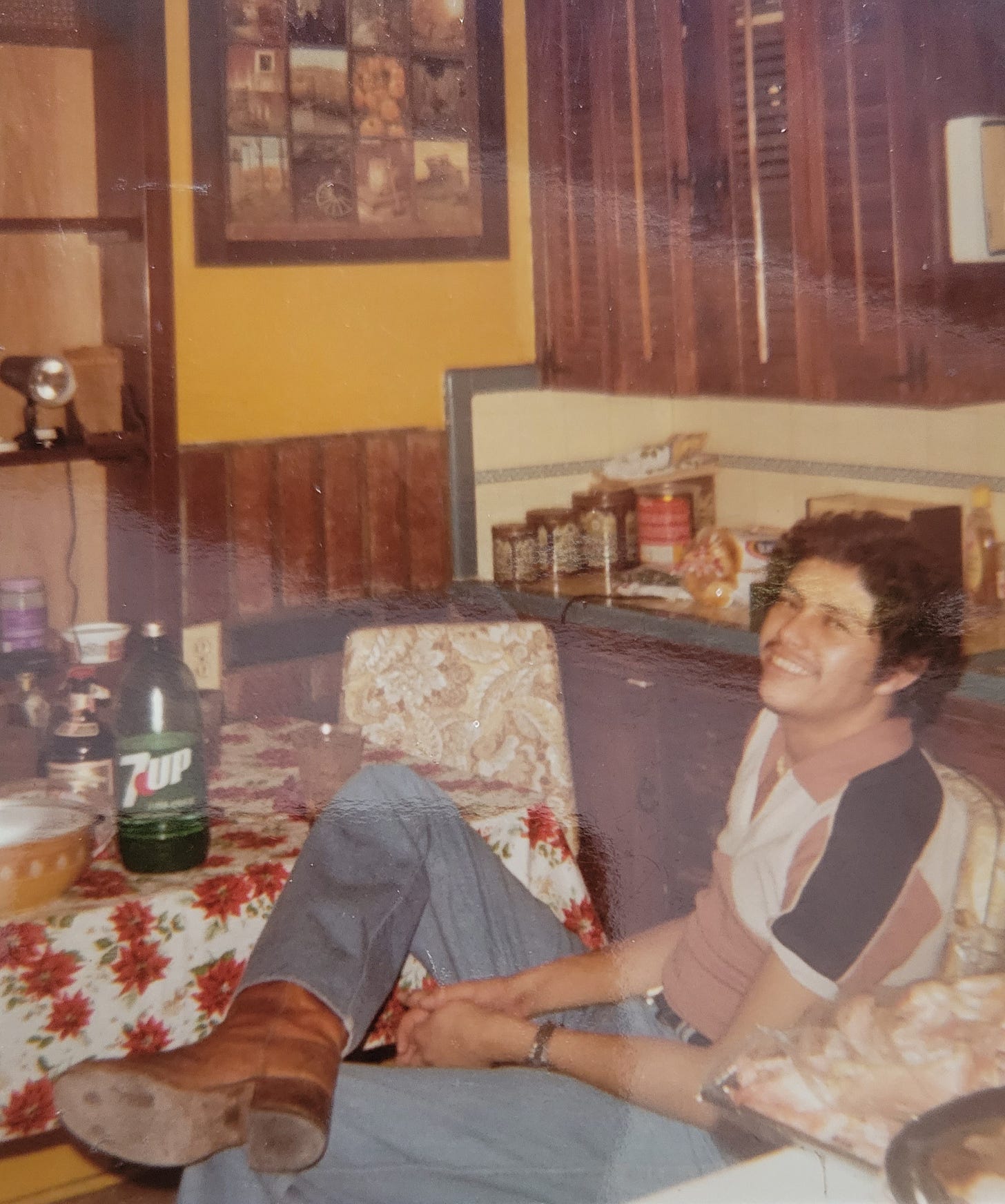

Just prior to my departure for the university I recall visiting him in a studio apartment in a part of town where your car might not be there when you return. We had made plans for lunch several days prior, but after several minutes of knocking on his front door, and from the smell that greeted me when he finally did open the door, I knew that he had been drinking all night and had forgotten all about our lunch date. As I sat on a sofa older than me, waiting for him to shower and dress, I couldn't help but see with new eyes the man before me.

There was a near empty bottle of Jack Daniels, an ashtray full of cigarette butts, a coffee table with an empty pizza box and a half eaten sandwich, and then there was the smell to contend with—a cocktail of stale vomit and Old Spice. As I allowed my eyes to wander his apartment I couldn't help but wonder what had happened to the man with all the fantastical stories, the magic in his voice, and most importantly, the man who I always believed could do and teach me absolutely anything. Was this the man now taking a shower in a filthy studio apartment who was too hung over to remember our lunch date?

A part of me wanted to stand up and walk out of there before he stepped out of the shower. But I didn't. I couldn't. I just wasn't able to bring myself to do what he had done to me in so many different ways throughout my childhood.

So I waited, and when he finally did emerge from the bathroom it nearly broke me to see how happy he was to see me. Maybe he didn't expect that I would still be there when he stepped out of the bathroom. And as I waited for him to put the finishing touches on his ensemble, I struggled to comprehend how it was possible that he could love me while persistently having failed me in so many ways over the years: the no-shows at the soccer games; the empty chair next to my mom at the music recitals; and everything I had achieved, he had missed. Yet there he was brimming with pride on the eve of my departure for the university, and part of me wanted to tell him that he had no right to any of the pride he was feeling because every drop of it could only belong to my mom—or anyone who may have helped her, and that wasn’t him. But I couldn't bring myself to say any of that because I could also see that there before me was a shadow of a man hanging on to life by a very thin thread, and what could possibly be gained by cutting that thread?

I also couldn't negate that I loved him. Not for the man he was, but for the man who had made the briefest moments of my childhood magical. Because little did anyone know, it was that magic that made so much of it bearable. And, because he made me believe that there was nothing that I couldn't achieve or do with my life.

Years later when I graduated from the university I remember sending him tickets to the ceremony in case he wanted to attend. I made sure that his seats were far away from my mother’s. But after the ceremony as we all stood in the lobby of the athletic center, where the event had taken place, he never actually came over to hug or congratulate his son. I think everyone there knew that I was lingering in that lobby because I wanted to see him, but nobody had the courage to tell me until much later that they had seen him leaving before the ceremony even concluded.

We didn't speak for a while after that. It took a while to understand why he couldn't bear to be there with me at my graduation. But I eventually concluded that being there in that auditorium made him see himself through my eyes and, without a doubt, it broke his heart to recognize how many ways in which he had failed me, and what I had achieved despite those failures.

By the time my mom had already legally went back to her maiden name and I had opted to do the same. On the one hand I couldn't see carrying the name of someone who wasn't man enough to stand there with me when I needed him. But mostly I made the change because I knew that my mom wanted me to make the change with her, and I didn't think I could deny her that small boon given all that she has done for me.

I reached out to my dad when I was about to marry, and surprisingly he agreed to let me pay for his tux and participate in the show. We started seeing each other more frequently, for meals and movies mostly, but there was an instance where he suggested we go camping together.

Hesitantly, I agreed.

Mostly because being alone in the wilderness without the buffer of waitresses, bartenders, or the self imposed silence of being in the cinema was unexpected. I always assumed that he liked having the buffer because it prevented me from demanding an explanation for all the broken promises and obligations, and yet there he was asking for a camping trip where there would be no buffer to save him—or me.

Weeks later, beneath a beautiful, panoramic mountain sky we sat next to a campfire and drank ice cold Modelo beers. The conversation was casual at first, but it wasn't long before he came to what he had brought me out there to say: he was sorry that he hadn't been there for me.

I admit, although his apology was far from eloquent it was substantive. Naturally, he made some excuses, mostly related to how unfair and unrelenting my mom had been in demanding his assistance over the years. If I was sympathetic, at all, it was only because I knew how relentless she could be to anyone who had wronged her. She would never be confused with someone who forgives and forgets, and to be on her bad side was to be in the crosshairs of a lifelong vendetta.

But our camping trip didn't make it until the second night, either because we both understood that the purpose had already been achieved, or, because, we were both eager to return to the safety of buffer zones where we could both leave the past where it was.

As we drove back to civilization I struggled with the dilemma of confronting him with the problem of his drinking. In the two days we were together he hadn’t stopped drinking once, and while the moment didn't seem appropriate to pull the drink from his hand, it did occur to me that by avoiding the eight-hundred-pound-gorilla-in-the-room I was failing him as a son. Perhaps not in the same way he had failed me, but nevertheless I was seeing a problem and doing nothing about it, a different shade to the same cowardice that had kept him from being the father I needed him to be. Was I, too, going to be a coward?

Apparently.

Of course, I justified my silence by telling myself that if fatherhood hadn't been sufficient motivation for him to seek help, then, there was likely nothing I could say to help him change now. Besides, I told myself that I no longer needed a father. Because just as he said I would, I had survived childhood, and I felt certain that I was on track to have the world at my fingertips, too.

I opened a rental and tours company in Sonora, Mexico, and decided to bring him in as a partner. I put up the investment, but still gave him his share of the company. I hoped that if he had something of his own maybe he would find the strength to ask for help, and when he did I would be there. But the plan backfired.

He just found new drinking holes and fell into them. I didn't have the patience to babysit both a business and him. And instead of the business bringing us closer together it proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

We had an argument about a contract he entered into on behalf of our company that we couldn't live up to because of a previous contract with another company. It should have been a minor oversight, but it turned nuclear and led me to say some very ugly truths that broke his heart. Not for the first time, apparently. I knew that I had said too much, and though I could have apologized, I let pride guide my actions and told him to leave.

I never expected to see him again. And though I was saddened by that prospect, I did nothing to change it, nor did he.

But years later when I was on trial for my life, I would look back over my shoulder from time to time and there he was. The father who had missed almost every soccer game, music recital, spelling bee, science fair, or graduation was the person who never missed a day of my trial. And when I started to see the writing on the wall, that the law was not going to be upheld and they were going to do whatever was necessary to find me guilty, despite what the evidence said or justice demanded, I would look over at him and he would smile and I would remember what he said to me on my tenth birthday: Son, life rarely waits until we're ready, and most of what will happen to us will be unpleasant, maybe even horrible. But even that's not a good enough reason to give up on it.

When the verdict was read he had both of our tears in his eyes, because though it was my life they had taken, I wasn't about to give them my tears, too. And that was the last I ever saw him.

Over the years I always thought he would write me a letter of encouragement, or maybe a few lines to inquire about the appeal process or my state of mind. I sent letters to some of the addresses I had for him, but most were either ignored or return-to-sender.

Whatever his reasons, the years of isolation provided me with an opportunity to better understand his condition as an alcoholic. Prison is filled with addicts of all stripes and colors, and there is no shortage of Alcoholic’s Anonymous meetings to attend.

I would sit in those meetings and listen to one man after another confess to having failed his family and friends in the very same ways that my father failed me. The more I read, listened, and watched the more I began to understand that he had a sickness and that condition was alcoholism.

I realized that I could have done and said so many things to try and convince him to seek help, but I was so centered on my goals and accomplishments that I didn't even consider that he needed my help. His siblings could maybe have done more, and there are a million things we could all have probably done differently to help bring him back to us. All of which accounts for nothing, because we didn't.

To most who knew him, he probably wasn't worth the trouble of rescuing. But I'm pretty sure that none of them knew the man that I did. The father who would catch me in his arms when he was seated in his recliner and he would fall back to the floor laughing hysterically. The father who never tired of peddling us around the city on his bicycle. The father who taught me to skip stones on the lake, shoot a slingshot, fling a Frisbee, tie the laces on my shoes, and above all to never give up on this magical experience we call life.

He died last year from COPD, alone in a nursing home and according to the caregivers at the home there was only one person who visited him and I don't even know who she was. I find myself in unfamiliar territory because I am grateful to that someone who I have never met; primarily because she was there when I couldn't be.

There is something singular about gratitude. And how best to express it has always been somewhat of a conundrum. Words can seem empty and sometimes even overly casual, while actions can be misinterpreted, which can leave us needing to express gratitude for things that we can't even put words to. And the best I have come up with is to find ways to pay it forward, to someone, somewhere.

I don't know what the hereafter will look like for all of us, but I have dreamed of mine many times and it's always the same. I’m on a beach with wet sand between my toes and a perfect breeze caressing my soul. There is a sunset on the horizon and there before me, seated with his arms around his legs is my dad. He's young, maybe early twenties or thirties, and he's been waiting for me.

I sit next to him on his right side and not a word is spoken as we stare out at the sunset. There is so much that I need to say, but the dream always ends before I do, and I can't help but think that maybe the dream ends because the part of knowing what to say is not yet written.

But that's not entirely true because I do know what I should say: Dad, none of that matters now. Be at peace and know that having had all the dads in the world to choose from I would still have chosen you. I'm sorry that I was ashamed of you. And I'm sorry that the time we shared together was so brief. But that's what life is, I guess, brief.

You were right about the storms of life trying to splinter me. You were also right, in that, just because something is difficult is not a good enough reason to give up on it—in fact, that might be the only reason to do it, and that's good enough. But here is something that you were wrong about. Having the world at our fingertips isn't something we wait for because it has always belonged to us, a sort of birthright, and the only question is whether we're brave enough to push beyond our fears to where that birthright resides. In your own life you may have failed to seize your own, but as a father you succeeded because whether you realize it or not, you helped me to push through my own fears more times than I can remember. Which means that together we succeeded.

I imagine that we eventually part ways on that beach, but not before hearing one last time, “this is me, is that you?” And I say, “yes, yes it is, because I am more you than you, and you are more me than me. I love you, dad.”