Independence days make me reminiscent on friendship and the people who otherwise lend texture to our tapestries. It's also a day that reminds me of the inevitability of all that is improbable. Whether we're talking about national revolutions for freedom or individual pursuits of success and happiness, what we're really discussing is the highly improbable, but nevertheless inevitable, outcomes in life. Obviously, I don't pretend to be an expert on the national revolutions throughout the world that eventually led to independence; but, history does present an undeniable and consistent truth: some of the most inevitable outcomes have also been the most improbable; an observation that perhaps deserves a moment's pause for reflection on the inevitable, but altogether improbable trajectories that our own stories have followed.

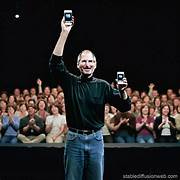

Recently, my mother emailed me something by Apple's co-founder Steve Jobs, written shortly before he died. I had probably already read some variation of it in one of his biographies—given the fact that he was certainly one of my living role models—but this time, his words had a different effect. My role model was dying from pancreatic cancer after having pursued any number of life saving options from the medical interventions of surgery to the spiritualism and positive thinking of the New Age. Here was a man, who despite all his success, wealth, fame, influence, and power: death had irrevocably taken a seat at the foot of his bed and would not be leaving alone—there would be no negotiations with corporate boards for reinstatement; and no amount of money would change his visitor's mind—and what he had to say was as succinct as it was clairvoyant.

He wrote: "material things lost can be found. But there is one thing that can never be found when it is lost—Life." His words reminded me of something he had said during his commencement speech at Stanford in 2005, where he said, "remembering that I'll be dead soon is the most important tool I've ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life...[and] remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose."

In the aforementioned commencement speech, he talked about his initial diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, about having to confront his mortality, and the sobering effect that had on his life and the decisions he made moving forward. It was a message I identified with because I had likewise received a diagnosis in my early 20s, that my life would be substantially shortened by a heart condition (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) where eventually my life would end through a massive heart attack—assuming that some other aspect of life didn't get to me sooner. But, unlike Jobs, I didn't have the world's foremost medically-inclined minds brainstorming on possibilities, nor did I have any of his aforementioned attributes that would get me on a transplant list. So, I didn't have a conversation with family and friends for the twofold reason that they couldn't offer a solution (so why add a worry or problem to their lives?) and the last thing I wanted was their sympathy.

Instead, the first thing I did was exactly what the doctor had told me not to do: pursue extended amounts of cardiovascular exercise, because with your condition that can lead to sudden death. Medical advice that explained the dizziness I had experienced whenever I pushed myself physically, but at that point it was advice that seemed counterintuitive to the very nature and essence of life: "either get busy living or get busy dying" (Shawshank Redemption). Asking me to stop running (or any of the other activities I loved) was like asking me to stop breathing. And, as I ran, in my own way I had a tête a tête with death, and, the outcome of that conversation led to my immediate renunciation from my otherwise promising career in finance, followed weeks later by my relocation to a small beach town in Sonora, where instead of managing investments I would take tourists on scuba and kayaking tours on the coast.

Call it an early-onset midlife crisis, or call it what is was: a wake-up call. What Jobs said in his commencement speech, was a truth that I had already confronted: "your time is limited, so don't waste it living someone else's life." And someone else's life was exactly what I was doing in finance.

In my tête a tête with death, the very first observation I made was that I quite literally did not care about returns on investments, interest rates, or the people I had to interact with on the daily. Yes, money and the management of assets and wealth is a corollary part of life in a capitalistic world, but to make the accumulation of ones-and-zeroes on mine or someone else's balance sheet the focal point of my existence, just seemed asinine. And, maybe renting jet skis and sunset cruises with dolphins was just as asinine in comparison to someone whose life is aimed at curing cancer or otherwise making the world a better place, but at least it afforded a few moments happiness to an otherwise pointless existence.

Unfortunately, the early-onset nature of my midlife crisis was short lived because I didn't avoid the very trap my role model would later speak on: "Don't be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people's thinking. Don't let the noise of others' opinions drown out your inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary."

What he was referring to was the very trap that I had fallen into. Because despite the fact that I was living in a beautiful place where almost every morning I could run on the beach, where there was great food, siestas in the afternoons, and cold beer in the evenings, I couldn't be happy since I had long ago accepted someone else's truth for my life: worldly success is a beauty contest on what you did, could have done, and maybe should have done relative to what others have done. Which meant that, the more time I spent playing Frisbee with my dog on the beach the more opportunity cost I was mentally accumulating on my balance sheet, a reality that was making me feel something I hadn't felt in a very long time—fear.

After all, what if I was wasting the best years of my life on a beach where I had seemingly given up on all of my dreams and ambitions? What about wanting to be the CEO of something important? Or, what about all the fun and glory that comes from achievements and greatness? These were the questions that began to haunt me. And actually, I eventually found myself trying to reason with my fear, only to find that fear isn't reasonable: it doesn't care about logic, good sense, impending death, or any other excuses we might have; all it cares about is making us see the truths that we would otherwise rather not see.

I was ignoring the best parts of myself because I was afraid to pursue something that I might not achieve because of a medical diagnosis that I could not control. Fortunately, my fear helped me to see that impending death isn't a good excuse, if anything it's more of a reason to be bold in our enterprises and fearless as we stand face-to-face with our mortality everyday when we look into the mirror. Because, as my role model said, "If you live each day as if it were your last, someday you'll most certainly be right." And, how would that be different from anyone else's life?

One of the dogmas of the western world is to fear and otherwise ignore death. We tend to see death as a tragedy, rather than what it truly is: the great equalizer that makes existence tolerable. I can't even begin to imagine the curse it would be to be stuck in the body of only one iteration of me for all eternity. Don't get me wrong, I love being me, but if life is anything like I suspect, there are countless variations of me that are waiting to be lived, and I'm both humbled and excited to live them. And since death is undoubtedly the doorway to all the infinite possibilities that life offers, why should it be feared?

Maybe my perspective on death is as improbable as it is inevitably wrong, but as we celebrate Independence Day isn't it the highly improbable but nevertheless inevitable outcomes that we're really celebrating?

Consider for a moment how improbable it must have seemed to any of the imperial superpowers of the world in the 18th century—England, France, Spain and Portugal—to even conceive of the possibility that a relatively novel idea like freedom could eviscerate their world. The Age of Enlightenment brought forth dangerous ideas through intellectuals like Denis Diderot ("Political Authority," 1751), who wrote, "[that] no man has received from nature the right to command others. Liberty is a gift from heaven, and each individual of the same species has the right to enjoy it as soon as he enjoys the use of reason." And within a couple of decades that idea manifested into the "Life, Liberty and Pursuit of Happiness," along with the idea that "all men are created equal" that became part of the Declaration of Independence.

It was unlikely that King George III, sitting on his throne of England's premiere position as the world's imperial superpower, could have foreseen the highly improbable but nevertheless inevitable outcomes headed his way when a young man from Virginia named Thomas Jefferson stepped on the political stage in America. Nor did he or his contemporaries understand the momentum of that same idea until it rolled through Haiti with Toussaint Louverture at the forefront, and then spread like wildfire in South America through the guidance of Simon Bolivar. Therefore, to celebrate American independence is to celebrate the entire movement of freedom and liberty that reinvented the known world.

As Steve Jobs stood before those newly minted graduates at Stanford, he wisely said, "You have to trust in something—your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever—because believing that the dots will connect down the road will give you the confidence to follow your heart, even when it leads you off the well-worn path, and that will make all the difference." I agree. And, as we celebrate independence we should be mindful of whether we are following the well-worn path or inventing our own paths along the way. Because at the end our lives when death appears, it might be untimely but not unexpected, and we should at least have the satisfaction of being able to look back at the path we forged, look at death with a smile, and say, I did that—and then maybe add, what took you so long?

If you enjoyed this please leave a heart

First Image: Courtesy of Freepik.com

Second Image: Courtesy of Fast.com

Third Image: RockyPoint.com

Fourth Image: Courtesy of OSX Daily.com